Dostoyevsky, the modern intelligentsia, the spiritual crisis of the West

Cicero will have his tongue cut out, Copernicus will have his eyes put out, Shakespeare will be stoned...

The revolutionary despises all doctrines and refuses to accept the mundane sciences, leaving them for future generations. He knows only one science: the science of destruction…

The Catechism of a Revolutionary, Nechayev (1869)

In short, one may say anything about the history of the world - anything that might enter the most disordered imagination. The only thing one cannot say is that it is rational.

Notes from the Underground, Dostoyevsky

I am perplexed by my own data and my conclusion is in direct contradiction of the original idea from which I start. Starting from unlimited freedom, I arrive at unlimited despotism.

Shigalev, in The Devils

Every age has its own divine kind of naivety for the invention of which other ages may envy it – and how much naivety, venerable, childlike and boundlessly stupid naivety there is in the scholar’s belief in his superiority, in the good conscience of his tolerance, in the simple unsuspecting certainty with which his instinct treats the religious man as an inferior and lower type which he himself has grown beyond and above – he, the little presumptuous dwarf and man of the mob, the brisk and busy head- and handyman of ‘ideas’, of ‘modern ideas’!…

Nietzsche

In democratic societies each citizen is habitually busy with the contemplation of a very petty object, which is himself.

Tocqueville

State socialism is on the march and there is no stopping it. Whoever embraces this idea will come to power.

Bismarck

Man in socialist society will command nature in its entirety with its grouse and sturgeons. He will point out places for mountains and for passes. He will change the course of rivers, and he will lay down rules for the oceans.

Trotsky

In summer 2000 I’d been working on the anti-euro campaign for 18 months, my first job in politics. I was overcome with disgust for Westminster (not the last time) and had broken up with a girlfriend. I flew to Naples for a week where I wandered the city and read The Devils in restaurants. I’ve just re-read it for the first time.

It’s amazing how it predicts so much of the 20th Century: the rise of socialism-communism, the spread of atheism, the psychology of violent Communist revolutionaries, the cancel culture of middle class liberals, totalitarianism — over and over we see many critical aspects of our world, on which ‘news’ and politics focuses, already there in Dostoyevsky’s picture of the period after the 1848 revolutions. And it all connects to politics today — here, in Europe, in America.

Many ask: what explains the spasm of weird madness that’s metastised across the world in the last decade, where did this insanity on campuses come from, what is this mind virus, how does it spread through the old media and the old institutions, what can beat it?

Much of the answer lies in the process of regime change and the emerging spiritual crisis of the West in the 1840s-70s.

Below are notes on The Devils. This is Part I.

Regime change and how our world rhymes with the 1840s-70s

The new literary scene in the 1860s and Fathers and Sons

The reaction

Backstory on Dostoyevsky’s life

Real events that inspired the book such as terrorism in Russia

Chernyshevsky’s What Is To Be Done?

Dostoyevsky’s response to WITBD: Notes From The Underground

Crime and Punishment: ‘a heart unhinged by theories’

Travel in Europe, writing The Idiot

Writing The Devils

Part II will discuss the novel. Over the summer I’ll re-read The Brothers Karamazov and blog on that too.

The ~50 Year Cycle of Regime Change

If you look back at European history since the French Revolution, there is a cycle of slow rot, elite blindness, sudden crisis, fast collapse, regime change that flares up roughly every 50 years.

Institutions are pulled apart by forces that are very powerful but act over timescales beyond an electoral cycle and even beyond individual careers — ‘forces’ including ideas like socialism or atheism, and social-material forces like automation and urbanisation.

We don’t have good theories for political change.

We don’t have good institutions for either long-term political operations or short-term crisis management. Failures of the former are then exposed by the failures of the latter. Individual and institutional OODA loops inevitably are often out of whack with reality, get more out of whack rather than less, then repeat errors. Although the West’s combination of markets plus science/technology does generate learning (companies die, startups replace them etc), our political institutions show little-to-no sign of learning in how they deal with things like state competition and war. Patterns of failure recur reliably hence books like Thucydides and Sun Tzu remain cutting edge.

What’s most important is what’s hardest to see and adapt to — by definition, an emerging new-true-important-idea will seem very odd and be unpopular because socially disruptive. The rare individuals who, partially and spectrally, see what’s happening are largely inevitably ignored, excluded, ostracised, sometimes killed. (Leaders like Pericles who can look at their own time and people with a cold outside-their-own-epoch eye and tell their people things like ‘your empire is seen as a tyranny’ are inevitably very rare.)

Even when the thing can be seen, a huge incentive asymmetry makes it hard for institutions to act and almost impossible for any individual to affect them much. Almost all hard things in politics/government require facing unpleasant reality and sticking to long-term operations that disrupt existing power and budgets. But the social/career costs for any individual pressing others to face reality, stick to long-term operations, and disrupt existing power and budgets are very high, immediate and personal, but gains are ephemeral, long-term, and accrue almost entirely to others. Therefore almost all large organisations incentivise (largely implicitly/unconsciously) preserving existing power structures and budgets, preventing system adaptation, fighting against the eternal lessons of high performance, excluding most talent, and maintaining exactly the thing that in retrospect will be seen as the cause of the disaster. Large organisations naturally train everyone who gets promoted to align themselves with this dynamic: dissent is weeded out. Anybody pointing out ‘we’re heading for an iceberg’ is ‘mad’, ‘psychopath’, ‘weirdo’ — and is quickly removed. And even the very occasional odd characters who a) can see the spectral signs, b) have the skills to act and c) have the moral courage to act are highly constrained in what they can do given the nature of large institutions and the power of the forces they confront. (Even Bismarck in 1871-5 or Stalin in the 1930s, more powerful than anybody else in their country, were highly constrained in their ability to shape forces like automation, though they could help or hinder their particular country’s adaptation.)

But ‘reality cannot be fooled’. Long-term forces collide with a) short-term forces, b) freak events (e.g X shoots Y, someone leaks the virus from the lab), and c) decisions-amid-fog-and-friction — and crises emerge.

Crises are inherently hard to predict, partly because they rely on sudden shifts in what ideas and behaviour humans copy (mimesis), and humans will be confused about and lie about what they’re thinking/feeling in crises.

Crises overwhelm inevitably bottle-necked institutions like overflow pipes in a flood and institutions collapse (e.g 1848, summer 1914, 1917, 1940, 1989-91, covid).

Collapse forces painful adaption. Amid crisis, live players grab apparently useful ideas that happen to be lying around — ideas generated perhaps by characters now dead and unrecognised in their lifetime, but who are suddenly discovered by artists (e.g Nietzsche) — and build new things in a mad scramble for power. And the cycle starts again…

The vast majority of Insiders cannot see this process while they are playing their part in it and even those who see some only ever see a little. The process only acquires any coherence in retrospect when it becomes history, people define a period including the run-up then the crisis and the regime change and try to abstract critical features of it and argue for centuries about the ‘causes’. Though even after it becomes ‘history’ it remains unsolved: we still can’t describe a good model for the cause of war in summer 1914, we still argue about whether the French Revolution was net good/bad, most find it impossible to learn much from the Cuban crisis even though we can listen to secret recordings of key meetings.

Looking back since the French Revolution and end of the Holy Roman Empire we see this cycle repeat.

A cycle of major war and revolution ended in 1815 with the Peace of Vienna.

In Germany the 1815 settlement nearly crumbled 1848-50, barely held, then was transformed in 1866-71 (~50 years) then again, after another ~50 years, in 1918 (Weimar), again in 1933 (Nazis) and 1945 (West/East Germany), then ~50 years of relative stability then again in 1989/91 (a re-united Germany).

France has had more regime changes depending how exactly you count them.

Russia had four: the Tsars, Communists, Yeltsin, now Putin (although nominally the Yeltsin constitution largely remains I think it’s more accurate to see the current regime as fundamentally different in a similar way as Prussia/Germany was fundamentally different after 1866-67 even though the old Prussian constitution remained).

The Habsburgs were chased out of Vienna in 1848 and had to fight their way back in, had to rejig the Empire after Italian and German unification, collapsed in 1918, that regime was replaced by the Nazis then replaced again in 1945.

And so on…

Sometimes regime change goes faster and wider as crises multiply (e.g 1848-71, 1917-19), sometimes it is more stable (e.g 1815-48, 1871-1914, 1945-89). But 50 years seems to be about the maximum then at least a few big regimes change. And even Britain and America, avoiding revolution and defeat, have seen a similar process of the regime being reinvented every 50 years or so (Washington/Hamilton, Lincoln, FDR, ??).

I think what’s happening now across the western world rhymes with this cycle.

1840s-70s redux

In the 1840s we can trace:

The old generation of Metternich et al who had lived through the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars were retiring and dying out. In the 1840s you can see their letters referring constantly to new dangerous forces, a satanic Zeitgeist, new ideas, new madness in the universities, the threat of revolution, a feeling that they were holding back ‘a streaming flood’ that could ‘wash away’ civilisation and bring back war. For example:

‘What can these little manoeuvres [conservative politics] possibly achieve against the onward pressing Zeitgeist which, with satanic cleverness, wages an unceasing and systematic war against the authority established by God… [nothing is able to stand] against the always freshly blowing wind of the Zeitgeist’. Leopold von Gerlach diary, October 1843.

‘Out of the storms of our time, a party has emerged whose boldness has escalated to the point of arrogance. If a rescuing dam is not built to contain the streaming flood, then we could soon see even the shadow of monarchical power dissolve.’ Metternich, 1844.

New ideas were spreading among the educated young particularly liberalism, nationalism, atheism and socialism.

New technologies were spreading, particularly the telegram and modern media. When the 1848 revolutions kicked off it was the first time news was accelerated by transfer of information from city to city in hours. Before this, news of an attempted assassination in Paris could take 10 days to get to the most powerful person in Europe, Metternich.

New material forces of urbanisation, free trade, industrialisation etc disrupted social relations therefore politics (e.g the guilds and artisans, agriculture and peasants).

The institutions of the ancien régime stretched and stretched but couldn’t cope. Metternich et al tried to build international and domestic institutions to control and guide politics to suppress the effects of liberalism, nationalism, atheism. But these forces were too powerful for the institutions.

Then:

A. Forces plus crises swamped the institutions: waves of revolutions, wars, and chaos from January 1848.

B. New countries and new regimes were formed: e.g Italy and Germany formed out of wars based on the propaganda of nationalism, France re-founded as a Republic after the brief, bloody Commune and red flag flying in 1871.

C. Regimes that survived were transformed. The Britain and Russia of the 1870s were radically different to the 1840s. Old conservatives such as Metternich and the Gerlachs in Prussia, conservatives truly committed to resisting liberalism and atheism by force if necessary, were swept away forever by the flood they foresaw. New conservatives such as Bismarck accepted the new ideas could not be suppressed. Nobody is sadder than me, said Bismarck, that the old regime had thrown the earth on its own coffin in 1848. Everywhere, oligarchic elites did what the Alcmaeonidae family had done in Athens when they invented democracy: i.e tried to appropriate the wayward and always somewhat hunter-gatherer-communist-inclined energy of the demos to their own aristocratic/oligarchic faction to bolster their power. Everyone was accommodating liberalism, nationalism, atheism, democracy and making concessions to socialism. Bazarov-like revolutionaries would have been locked up or flogged by the old regime; now they became literary sensations and real-life celebrities (with London as a revolutionary-terrorist haven). Traditional/mainstream ‘Conservatives’ were blown helter skelter by ideas and material forces they struggled to understand, shape or master. They’ve never stopped being blown since. A new ‘meritocratic’ civil service developed in Britain and elsewhere that sucked power into itself and generated future crises.

D. By the 1870s there was a clear spiritual crisis of and in the West. This spiritual crisis is clearest in Dostoyevsky and is the story of his major novels, and in Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil. This spiritual crisis was upstream of political developments in coming decades

We’re into a new cycle of regime change

We’re experiencing something very similar to the 1840s-70s.

The old generation who fought in World War II has retired and is mostly dead. Their personal memories of the bloodshed are no longer part of discussions in Cabinet rooms. The people who really studied nuclear weapons have almost all died/retired and their successors in Cabinet rooms — even those personally responsible for briefing leaders on Great Power confrontation and nuclear escalation today — are often ignorant of the dynamics of summer 1914 and the dynamics of the Cuban crisis.

New technologies are spreading, most obviously AI, robotics, and biological engineering. Along with great gains will come faster and more destructive disasters (as von Neumann predicted in Can we survive technology?).

New social-material forces: industries being totally disrupted, large categories of employment facing automation with large political consequences (e.g roughly 0% of SW1 are aware that ~100% of customer support can now be automated by LLMs that barely hallucinate, the limiting factor in replacing all this human labour is the world’s friction not scientific progress).

The spiritual crisis visible from the 1860s-70s, politically briefly less explosive in the 1990s after the relieved tension of 1989-91, is all around us and bubbling up in new forms. It’s not coincidental that Dostoyevsky and Nietzsche are much quoted today in the WhatsApps of the most powerful billionaires, or that Wang Huning, perhaps the most-powerful-not-famous-politician, studied this intensely (cf. America Against America) and Leo Strauss is now more studied in Beijing than in D.C. New mutant versions of old ideas are spreading among the educated young, including a new joy in ideas of violent revolution and rejection of Anglo-American liberalism and capitalism. ‘Rationalism’ is self-sabotaging, as Aristophanes described in The Clouds — the world’s first stab at Rationalism being 5th Century Athens — and as Dostoyevsky depicted in Notes from the Underground and Crime and Punishment. And the far Left today is most determined to attack and destroy liberals such as JK Rowling, just as we see in the rows between the generations in the 1840s-70s and in the determination of Nechayev et al to destroy the liberals first.

The old institutions of the ancien régime have stretched and stretched but can’t cope, they are hollow and disintegrating. The old parties like the GOP, Democrats, Tories, Labour; the old bureaucracies and institutions like the Cabinet Office, the US national security state, the EEC/EU, UN and NATO forged by World War II and the Cold War, the WHO, IMF etc; the old universities of Oxbridge and Ivy League; the old media like the BBC and NYT that created ‘consensus reality’ since 1945; the old scientific institutions for peer review and publication (hijacked during covid to spread misinformation about misinformation) — they’re all disintegrating in a self-reinforcing cycle of collapsing performance, collapsing trust and moral authority, spreading chaos, growing accusations of ‘madness’, and a widespread feeling that our system has been stretched to or beyond some invisible-but-critical threshold.

Institutional failure has become increasingly pathological, a doom loop that seems to spin faster and deeper each year. Our ancien régime shows less awareness of its crisis than their equivalents of the 1840s and instead of accepting any errors, each failure has led to further doubling down. There is not just no learning but what seems like a form of anti-learning, a bitter-hostility-to-learning.

Brexit and Trump in 2016 were signs of the coming floods and the doom loop. After Insiders were stunned by defeat, they doubled down on a weird mix of creating and spreading lies then believing their own lies, such as the ‘Russia-gate’ hoax — misinformation about misinformation created by Democrats to exonerate themselves for the incompetence of the Hillary campaign and to undermine Trump in Washington, and spread by some who knew it was fake and some who didn’t. Then they blamed the voters for being ‘fooled by misinformation’. After covid, across the West there was practically no interest across the political spectrum in facing the extreme failures of the old bureaucracies and fixing them; instead, everybody has rallied in their defence against ‘populism’. After covid and Ukraine, across the West there has been an extreme resistance to even discussing issues of procurement and industrial capacity that are absolutely central to our failure: even in a war of attrition, the old institutions won’t engage with our procurement horrorshows. Instead, our pathological old regimes have done all they can to distract attention, and themselves, from the failure of core institutions. They close things that work such as vaccine research and sewage monitoring. They continue with abject failures that kill people and guarantee disaster such as systems for procurement and energy.

Faced with collapsing trust in them, they deny it is justified by their performance and instead are trying to stand athwart history shouting ‘just go back to trusting us, let’s all go back to the wonderful nineties, don’t be fooled by misinformation, don’t support FASCISM’. The regimes push: higher taxes, higher debts, more wars they then botch, visible collapse of state authority over borders and citizenship, more political centralisation that makes crises worse, more hostility to entrepreneurs and those who can build and create value. When the voters rebel, Insiders respond by telling themselves that the real problem is the voters — so the solution is not ‘we should listen more and adapt’ but ‘we mustn’t listen to these idiots, we must find new ways to defend the old power structures’. They’re also now trying to mobilise hatred for out-groups — particularly Russia and China — in ways that resemble how regimes worried about losing domestic power behaved pre-1914. They parrot slogans from decades ago — ‘the special relationship’, ‘the rules-based international order’ — but we can see the hollow reality behind the rhetoric. So can non-NATO regimes across the world which are rapidly distancing themselves from and hedging against our repeated vandalism (Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, breaking our own global financial system after January 2022 etc).

This cannot work. Everybody outside the Insider social network holds our political regimes in contempt — the young revolutionaries and the young billionaires agree on one thing, politics is rotten and politicians seem deranged.

So I think (per my 2013 essay on politics and education) that we’ll hit events resembling 1848-71:

A. Waves of financial crises, revolutions, wars, and chaos.

B. Over the next 10-20 years a very different world will emerge and some of our regimes that seemed permanent, like the Soviets in 1980, will be replaced. Perhaps like the 1860s-70s new countries will be formed.

C. Regimes that survive will be transformed and the elites in charge will be transformed.

D. The political chaos will be downstream of the spiritual crisis described in Dostoyevsky: the crisis of ‘modernity’ itself and ‘rationality’.

See the bottom of this blog for a different way of framing the crisis sketched above.

A summary:

Our political Insiders en masse are even less able to see what’s happening than in the 1840s or 1910s or 1930. They understand less about relevant technology than in the days of cavalry and less about the emerging information ecosystem than in the days of mass audience newspapers (e.g TikTok).

The speed and scale of crises, the implications of institutional failure, have grown. In 1815 it took ten days for news of an assassination to get from Paris to the most powerful person in the world; by 1848 the telegram beamed news from city to city in hours and we see in 1866 the first war affected by rapid communication. Today we face nuclear crises that could escalate hundreds of times faster than July 1914.

The complexity of interconnected forces and human memetics has increased.

The quality of political Insiders and officials has collapsed as high talent has migrated (startups, hedge funds, mixes of maths and money etc).

The spiritual crisis is deeper.

And the institutions for crisis management are roughly the same as July 1914, as I wrote in 2019 and witnessed in 2020.

And if you want to explore the 1840s-70s in detail, how one man tried to surf this chaos and create a new world, read my chronology of Bismarck.

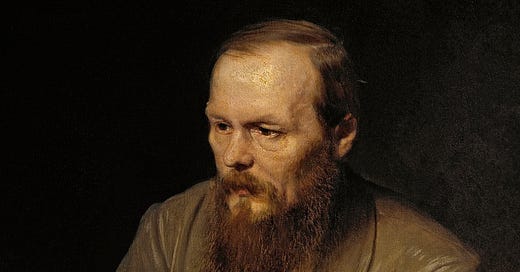

It’s a perfect moment to reconsider Dostoyevsky’s view on the struggle over western ‘values’ as we now call them, echoing Nietzsche who called Dostoyevsky ‘the only psychologist from whom I learned anything’. Our political crisis takes its most dramatic form in the war between the West and Russia that is a grotesque absurdist mix of 1914 trenches, AI-controlled drones, spiritual-clash-in-memes-on-social-media, and the lurking possibility our Idiocracy might stagger into nuclear Armageddon and a hundred Auschwitzs in an afternoon.

In 2022 I wrote about War and Peace. The more non-fiction I’ve read the more obvious it’s seemed that some aspects of politics and power are far better described by great artists than they are, and probably ever can be, by academics/scholars. Tolstoy’s description of how meetings really work at the apex of power in a crisis tells you far more than academic studies, which usually overrate the seriousness of the people involved and underrate the absurd, the vanity, the farce — and tell you far more than the absurd official Covid Inquiry (by lawyers, for HR) will tell you about what really happened. And you can’t understand a lot of history without understanding the artistic fashions of the times. You can’t understand the spiritual crisis of the West without reading Fathers and Sons, The Devils etc.

Many of these themes were also explored in my blog on Oakeshott and Rationalism.

I highly recommend Frank’s epic biography of Dostoyevsky from which much of the below is taken.

[NB. Some spoilers so don’t read until you’ve read the novel if you’re going to.]

{Slightly edited, typos etc 20/6/24}

Part I

This was the time, when, all things tending fast

To depravation, speculative schemes —

That promised to abstract the hopes of Man

Out of his feelings, to be fixed henceforth

For ever in a purer element —

Found ready welcome…

Wordsworth, The Prelude

The new literary scene in the 1860s and Fathers and Sons

In the 1860s a new generation of the intelligentsia burst onto the Russian scene. Mikhailovsky, one of them, described it as ‘the raznochintsy arrived. Nothing further happened.’ The raznochintsy were the sons of priests, petty officials, impoverished landowners — a class of people who had acquired an education, who had read older liberals and radicals such as Herzen and Turgenev, and who saw their hero as Belinsky, a raznochinets like them. Tolstoy himself said, rightly:

All this is Belinsky! He spoke at the top of his voice and spoke in an angry tone … and … this one [Chernyshevsky] thinks that to speak well one has to speak insolently and to do so one has to stir oneself up.

Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons (often translated Fathers and Children) sensationally appeared in spring 1862. Bazarov, the son of an army doctor like Belinsky, was the new literary image of the new radical. Bazarov ‘personified the split between the gentry liberal intelligentsia of the 1840s and the radical raznochintsy of the 1860s’ (Frank). Turgenev had studied the writings of the emerging generation. He simultaneously sympathised with them, deplored aspects, and feared for their consequences. One Soviet critical called it ‘a lapidary artistic chronicle of contemporary life’. The liberal/radical camp split along generational lines. The new generation contemptuously dismissed the old. Herzen’s generation was shocked by their aggression and their dismissal of art.

Turgenev wrote years later that when he returned to Petersburg on the day of the notorious fires, the word Nihilist was on the lips of thousands and the first thing a friend said to him was, ‘Look what your Nihilists are doing, they are setting Petersburg on fire!’

Frank writes that the book inaugurated the dominant theme of Russian intellectual life in the 1860s: ‘the conflict between the narrow rationalism and materialism upheld by this new generation and all those “irrational” feelings and values whose reality they refuse to acknowledge.’ Bazarov aggressively deprecates art. Throw away that rubbish, Bazarov says of Pushkin, and read Büchner’s Force and Matter instead. Raphael is ‘not worth a brass farthing’ and ‘a good chemist is twenty times as useful as any poet’. Bazarov even argues that while there are specific sciences we should not expect to find any deeper principles connecting them — everything is just ‘sensations’ and ‘there are no general principles’.

This attack on all general principles is the basis for Bazarov’s ‘nihilism’. The term had just come into use and Turgenev made it famous. A nihilist is, Arkady says, ‘a man who does not bow down before any authority, who does not take any principle on faith, whatever reverence for that principle may be enshrined in’. One of the elder gentry complains that ‘you deny everything, or speaking more precisely, you destroy everything. … But one must construct too, you know?’.

Bazarov replies:

That’s not our business now… The ground has to be cleared first.

Although the destruction is supposedly to prepare the ground for improving the condition of the people, in whose name the destruction will be carried out, for Bazarov the real focus is the destruction, not the distant future. On one hand Bazarov is proud to be a pleb and points out the peasants are more at home talking to him. On other hand, he mocks their superstitions and backwardness. In one scene, Arkady remarks on how Russia would advance when the poorest peasants had much better material lives. Bazarov confesses to a feeling of intense hatred for the poor peasants — he’s ready to ‘jump out of my skin’ to help them but they ‘won’t even thank me for it’ — they’ll be living in a nicer hut ‘while nettles are growing out of me’.

This is a great foreshadowing of the 20th Century revolutionaries such as those who sat around the table with Stalin in the 1930s. On one hand, radicals were dedicated to ‘serving the people’ but on the other hand the radicals were profoundly alienated from ‘the people’ by their ideas and education. On one hand ‘we’re doing this for the people’ but on the other hand ‘we hate the backward ignorant people and are happy to sacrifice them for our ideas of a better future’. On one hand an apparent rejection of egotism in the name of helping others but on the other hand in reality a supreme egotism, a supreme belief in the value of one’s own ideas and feelings and the morality of imposing them on the world.

But Turgenev presents Bazarov as the character with the energy and the impetus of an idea for the future while the old gentry seem relics.

Your sort, you gentry, can never get beyond refined submission or refined indignation, and that’s a mere trifle. You won’t fight … but we mean to fight … we want to smash other people. (Bazarov to Arkady)

One can see ideas that took hold in Crime and Punishment and The Devils — for example, Raskolnikov’s idea that there are ordinary and extraordinary people and the latter are morally permitted to commit crimes.

The reaction

Frank writes that do his dying day Chernyshevsky thought that the novel was a revengeful lampoon of Dobrolyubov, a literary critic and revolutionary. Chernyshevsky’s allies viciously attacked Turgenev.

Most took Fathers and Sons to be a condemnation of Bazarov and the secret police agreed in a report of 1862.

Turgenev was lionised by reactionaries, vilified by most radicals, and praised by some for glorifying Nihilism.

Dostoyevsky’s reaction was different. He read Fathers and Sons in 1862 when it was published in a magazine. He wrote to Turgenev admiringly. There was, he thought, a tragic conflict between Bazarov’s western ideas and his Russian heart he could not suppress. Turgenev replied that he had ‘so sensitively grasped what I wished to express in Bazarov … It is as if you had slipped into my soul… I hope to God … everyone sees even a part of what you have seen.’ A month later he added that ‘no one, it seems, suspected that I tried to present [Bazarov] as a tragic figure — and everyone says: why is he so bad? - or - why is he so good?’

Frank writes that Strakhov’s review echoed much of Dostoyevsky’s view. While most argued Bazarov was good or evil, Strakhov wrote that the true meaning was the conflict between Bazarov’s ideas and life. He is superior to the other individuals but not superior to the forces of life they embody. He disapproves of nature but Turgenev depicts nature in all its beauty. He does not value friendship but Turgenev depicts the reality of it in his heart. He rejects family sentiment but Turgenev describes the unselfish love of his parents. He scorns art but Turgenev describes him with art. Bazarov is trying to rebel against man’s core emotional nature but he cannot succeed, as nobody can.

Turgenev was upset by the general reaction to his novel and found it was only in a circle around Dostoyevsky and the magazine Time that he found people who understood what he meant.

Some backstory on Dostoyevsky’s life

Dostoyevsky read socialists such as Proudhon and Saint-Simon as a young man. He got to know Belinsky, a leading ‘Westerniser’. He became a member of an illegal revolutionary conspiracy, the Petrashevsky Circle, founded by an aristocratic character who was possibly an inspiration for Stavrogin in Devils. He was arrested, suffered a mock execution, but was reprieved and jailed in Siberia.

After release he became part of the literary scene. His House of the Dead astonished many. Tolstoy would later place it (in his What is Art?) among the few works in world literature that were models of a ‘lofty religious art, inspired by love of God and one’s neighbour’. Turgenev described the bath house scene as ‘Dantaesque’, the scene in which he described the convicts steaming and lashing themselves with birches:

It occurred to me that if one day we would all be in hell together it would be very much like this place.

He saw in Siberia and described how people would do things to assert the existence of their own personalities — things that could not be justified or explained by any rationalism, materialism or utilitarianism, things that were more like a man buried alive and coming to beating on the coffin lid, not in the hope of being saved, not as a question of ‘reason’. He rejected Chernyshevsky’s idea that ‘the environment’ was the overwhelming influence on behaviour. He rejected the idea that pure love for one’s neighbour is ‘really’ a supreme egoism.

In 1862, after the furore over Fathers and Sons, he visited France and found the French ‘nauseating’ then on to London:

Even externally, what a contrast, with Paris! This city day and night going about its business, enormous as the ocean, with the roaring and rumbling of machines, the railroad lines constructed above the houses (and soon underneath the houses), that boldness in enterprise, this apparent disorder which is, in essence, a bourgeois order to the highest degree, this polluted Thames, this air filled with coal dust; these magnificent parks and squares and those terrifying streets of a section like Whitechapel with its half naked, wild and starving population. The City with its millions and the commerce of the universe, the Crystal Palace, the World’s Fair…

He described how every Saturday night half a million of the working classes with wives and children would swarm through streets to enjoy their one day of leisure:

All of them bring their weekly savings, what they have earned by hard labour and amidst curses... It is as if a ball had been organised for these white negroes. The crowd pushes into the open taverns and in the streets. They eat and drink. The beer halls are decorated like palaces. Everybody is drunk but without gaiety, with a sad drunkenness, sullen, gloomy, strangely silent. Only sometimes an exchange of insults and a bloody quarrel breaks the suspicious silence, which fills one with melancholy. Everyone hurries to get dead drunk as quickly as possible so as to lose consciousness. [Touché!]

After wandering through a crowd at 2am on a Saturday night, he recorded that ‘the impression of what I had seen tormented me for three whole days’. On another evening he walked among the hookers of Haymarket. Frank points out the similarity of some passages with passages from Engels around the same time.

In Winter Notes he would later describe London as ‘Baal’, the false god of the flesh execrated in the Old Testament. This god of materialism was now the false god of the West with the World Fair embodying mechanised degradation.

You observe these millions of people, obediently flowing from all over the world — people coming with one thought, peacefully, unceasingly, and silently crowding into this colossal palace; and you feel that something has been finally completed and terminated. This is some sort of Biblical illustration, some prophecy of the Apocalypse fulfilled before your eyes. You feel that one must have perpetual spiritual resistance and negation so as not to surrender, not to submit to the impression, not to bow before the fact and deify Baal, that is, not to accept the existing as one’s ideal…

Here [in London] you no longer see a people but the systematic, submissive and induced lack of consciousness…

[At the heart of the problem of the external splendour built on misery was] the same stubborn, dumb, deep-rooted struggle, the struggle to the death between the general Western principle of individuality and the necessity of somehow living together, of somehow establishing a society and organising an ant-heap.

It was reported back to Russia by the secret police that he had met with the exiles Herzen and Bakunin (the latter had recently made a sensational escape from Siberian exile via America). While he did meet Herzen it is not clear whether he met Bakunin. He went on to Italy and read Hugo’s Les Miserables.

In January 1863 he was back in Petersburg then the Polish rebellion broke out (for the politics of this, see my Bismarck chronology). It began with a massacre of sleeping Russian soldiers then the Poles demanded the borders of 1772 and the return of Lithuania and much of Ukraine. Those radicals who sided with the Poles, like Herzen and Bakunin, lost any influence in Russia. A complex and misunderstood article in Time led to its suppression, much to Dostoyevsky’s anger and resentment (since he had not sided with the Poles).

Chernyshevsky’s What Is To Be Done?

In 1863 Chernyshevsky published the Utopian novel about a socialist paradise, What Is To Be Done? He was inspired by Hegel, Fourier, Feuerbach, Belinsky and Herzen. He cheered the 1848 revolutions. He was imprisoned in July 1862, wrote his famous novel, and had it published from jail — ‘perhaps the most spectacular example of bureaucratic bungling in the cultural realm during the reign of Alexander II’ (Frank)! In many ways and with many people this novel was more influential than Marx on revolutionary thinking post-1848. It generated ‘an indescribable commotion, much of which derived from its polemical relation to Fathers and Children’ and was ‘one of the most successful works of propaganda ever written in fictional form’ (Frank). Lenin himself was one of those strongly influenced.

It praised the moral virtues of the ‘new people’ whom Turgenev had maligned as Nihilists. Like Bazarov, its two male heroes were raznochintsy and medical students. They follow ‘rational egoism’ and, unlike Bazarov, escape their romantic feelings. In Utopian style it presented solutions to ancient problems as easy: the relationship of the sexes, new institutions, the transformation of mankind into an earthly paradise. All you have to do is accept that rational egoism compels one by logic to identify rational self-interest with that of the greatest good of the greatest number. They ridicule the ethics of self-sacrifice though they behave exactly according to its precepts. But they do not feel it as self-sacrifice. Lopukhov decides that the pleasure of giving up all material advantages and honours for himself is ‘the best utility for him’. He is worried only about whether he has somehow tricked himself into making a sacrifice when he’s trying not to!

Rakhmetov is a revolutionary superman, self-mastery toughened on a bed of nails, a Bazarov ‘wholeheartedly absorbed in his cause’ and ‘deprived even of the few remaining traits of self-doubt and emotional responsiveness that make [Bazarov] humanely sympathetic’ (Frank).

And the icon of this glorious socialist Utopia was … the London World’s Fair (see above)…!

Dostoyevsky’s response to WITBD: Notes From The Underground

Dostoyevsky started writing a reply to Chernyshevsky. The reply morphed from a review to his novel, Notes From The Underground (NFTU). He wrote it while his wife was dying before his eyes and his own health was terrible.

After the first section was published in 1864, he was appalled at the ‘swinish censors’ who had let through passages that blasphemed then censored the sections on the need for faith and Christ — ‘Are they conspiring against the government or what?’

Perhaps the censors were as disoriented as the critics, for Frank says that NFTU, like other examples of first-person satirical parody, was generally misunderstood until the 1920s and was treated simplistically by intelligentsia critics. For Frank, the Swiftian parody has been continually obscured by the artistic triumph of the creation of the character and therefore NFTU has continually confused people (p416).

NFTU was a clear attack on the ‘rational egoism’ of WITBD. It was a depiction of a particular social-ideological type that had evolved in Russia recently amid successive waves of European influence.

The underground man is paralysed, knows it, and derives a perverse pleasure from it. An intelligent man in the 19th Century must be ‘pre-eminently a limited creature’. And his ‘hyperconsciousness’ made him capable of recognising his enjoyment in his degradation. His reference to the ‘fundamental laws of hyperconsciousness’ is a parody of Chernyshevsky’s assertion that free will does not exist and everything is just ‘the laws of nature’. How can one take revenge if everything is ‘the laws of nature’? Whatever you look at —

You look into it, the object flies off into air, your reasons evaporate, the criminal is not to be found, the insult becomes fate rather than an insult, something like a toothache, for which no one is to blame.

The inevitable result of understanding the world as ‘just the laws of nature’ is a paralysing inertia, ‘conscious sitting on one’s hands’, because the only action is a sort of spite which is not a valid cause for any action, but the only thing left when the ‘laws of nature’ make any justified response impossible.

It would follow, as the result of hyperconsciousness, that one is not to blame for being a scoundrel, as though that were any consolation to the scoundrel, once he himself has come to realise that he actually is a scoundrel.

Reason tells the underground man that emotions like guilt or revenge are irrational and meaningless — yet they still exist! The underground man refuses to be consoled by his knowledge that the laws of nature are to blame, for his toothache, for his liver pain, for his feelings.

NFTU portrays the refusal of the human spirit to surrender its right to self-assertion — even at the price of madness and self-destruction. He wrote in his notebook that it’s impossible to love man as oneself, according to the commandment of Christ, as ‘the law of personality on earth binds. The Ego stands in the way.’ For Dostoyevsky, the great significance of Christ was as the enunciator of this morality — the message of love and self-sacrifice. For him, like Pascal, the most hideous idea was that the world is senseless.

When the underground man talks to an intellectual who believes everything is ‘the laws of nature’ but who does not realise this makes all his actions meaningless, a man without hyperconsciousness, ‘I envy such a man till my bile overflows’! The underground man is pulled apart by the tension between his intellectual acceptance of Chernyshevsky’s determinism and his spiritual-emotional rejection of it. His life is the reductio ad absurdum of the pure Bazarov pushed to its logical conclusion.

In short, one may say anything about the history of the world — anything that might enter the most disordered imagination. The only thing one cannot say is that it is rational. The very word sticks in one's throat...

After all, there are continually turning up in life moral and rational people, sages, and lovers of humanity, who make it their goal for life to live as morally and rationally as possible, to be, so to speak, a light to their neighbours, simply in order to show them that it is really possible to live morally and rationally in this world. And so what? We all know that those very people sooner or later toward the end of their lives have been false to themselves, playing some trick, often a most indecent one. Now I ask you: What can one expect from man since he is a creature endowed with such strange qualities?

Shower upon him every earthly blessing, drown him in bliss so that nothing but bubbles would dance on the surface of his bliss, as on a sea; give him such economic prosperity that he would have nothing else to do but sleep, eat cakes and busy himself with ensuring the continuation of world history and even then man, out of sheer ingratitude, sheer libel, would play you some loathsome trick. He would even risk his cakes and would deliberately desire the most fatal rubbish, the most uneconomical absurdity, simply to introduce into all this positive rationality his fatal fantastic element. It is just his fantastic dreams, his vulgar folly, that he will desire to retain, simply in order to prove to himself (as though that were so necessary) that men still are men and not piano keys, which even if played by the laws of nature themselves threaten to be controlled so completely that soon one will be able to desire nothing but by the calendar. And … even if man really were nothing but a piano key, even if this were proved to him by natural science and mathematics, even then he would not become reasonable, but would purposely do something perverse out of sheer ingratitude, simply to have his own way. And if he does not find any means he will devise destruction and chaos, will devise sufferings of all sorts, and will thereby have his own way. He will launch a curse upon the world, and, as only man can curse … then, after all, perhaps only by his curse will he attain his object, that is, really convince himself that he is a man and not a piano key! If you say that all this, too, can be calculated and tabulated, chaos and darkness and curses, so that the mere possibility of calculating it all beforehand would stop it all, and reason would reassert itself - then man would purposely go mad in order to be rid of reason and have his own way! I believe in that, I vouch for it, because, after all, the whole work of man seems really to consist in nothing but proving to himself continually that he is a man and not an organ stop. It may be at the cost of his skin! But he has proved it...

And the underground man rejects the Crystal Palace as the epitome of rationality — in the Palace, suffering is unthinkable, ‘suffering is doubt, negation, and what kind of Crystal Palace would that be in which doubts can be harboured?’ Doubt means one has not accepted determinism in full, one has not accepted man as a rational machine. So the underground man declares that ‘suffering is the sole origin of consciousness’.

The underground man is vain and enraged by the pointlessness and emptiness of his vanity. He overvalues intelligence to an extreme degree and describes how he grew up immersed in books. The books of the utopian socialists destroyed his ability to feel — he spent his time reading ‘to stifle all that was continually seething within me’. The vanity and self-importance, the intellectual superiority, are comical given his actual position in society and the comedy drives him mad with ‘hyper-conscious’ bitterness.

When the underground man visits the brothel, he is pleased when he catches sight of himself in a mirror and looks disgusting — ‘I am glad that I shall seem revolting to her, I like that’. After sex he then delights in overcoming her hostility with his revolting eloquence and fake-but-not-all-fake pathos until she breaks down in tears. He invites her to abandon her life and come to him — then is appalled by how when she comes to his flat she will see his shabby life! Over and over, he daydreams appalling dreams in which his nobility is recognised by others, even though he knows he has no nobility.

It is when he is enraged and impotent at his imperturbable servant that she reappears and of course he tries to humiliate her again:

I vented my spleen on you and laughed at you. I have been humiliated so I wanted to humiliate. I had been treated like a rag so I wanted to show my power. And I shall never forgive you for the tears I could not help shedding before you just now, I shall never forgive you, either.

And Liza then throws herself into his arms to console him! And he realises that she is the heroine and he is crushed and humiliated. So he again has sex with her — then pushes a five ruble note into her hand!

But I can say this for certain: though I did that cruel thing purposely, it was not an impulse from the heart, but came from my evil brain. This cruelty was so affected, so purposely made up, so completely, a product of the brain, of books, that I could not keep it up for a minute.

He then wonders whether perhaps she will not be better off always living with the outrage, perhaps living with the outrage will purify her.

And, indeed, I will at this point ask an idle question on my account: which is better, cheap happiness, or exalted suffering? Well, which is better?

His brain, his books, his western education is the root of his evil. And at the end the underground man uses ‘the idea of purification through suffering as an excuse for his moral sadism’ (Frank).

Leave us alone without books and we shall at once get lost and be confused – we will not know what to join, what to cling to and what to hate, what to respect and what to despise. We are even oppressed by being men – men with real, our own flesh and blood blood, we are ashamed of it, we think it a disgrace and try to be be some sort of impossible generalised man.

The censors butchered a crucial chapter in which Dostoyevsky explained the necessity of faith and Christ. The original was never restored. I won’t go into the details of trying to restore a picture of what he really meant — cf. Frank’s chapter for details.

I was shocked to read in Frank that ‘No one really understood what Dostoyevsky had been trying to do’ (with only a few exceptions) and he probably regarded his polemic as a failure, ‘as indeed it was, if we use as a measure its total lack of effectiveness as a polemic’ (p440).

His brother died shortly after finishing. He took on his brother’s magazine and its debts. The project failed. For the rest of his life he had to cope with the fallout from the debts he incurred. He soon had to flee to Europe to escape his creditors.

Crime and Punishment: ‘a heart unhinged by theories’

Strepsiades: Ah me, what madness! How mad, then, I was when I ejected the gods on account of Socrates!... For what has come into your heads that you acted insolently toward the gods, and pried into the seat of the moon? [The first ‘rationalists’ are recognised as a cultural plague, the Socratic thinking shop is burned down…]

The Clouds

In 1865 he started writing Crime and Punishment with the first parts published in early 1866. Then in April 1866 there was an attempted assassination of Alexander II by a student radical. There was a fierce reaction from the regime. Dostoyevsky thought that repression would be counterproductive and the more Nihilist ideas were permitted the less attractive they would be and the more Russians would laugh at them. This was the emotional atmosphere in which he finished Crime and Punishment.

Raskolnikov comes to realise that he does not know why he murdered the old woman. He starts off telling himself that he murdered for altruistic motives but finally realises it was pure selfishness.

He lives amid revolting squalor and misery. We hear familiar utilitarian arguments from supporting characters. Marmeladov’s family are kept from starving by the sacrifice of his daughter, Sonya, who has become a prostitute to feed the family. He tells Raskolnikov:

Mr Lebezyatnikov, who keeps up with modern ideas, explained the other day that compassion is forbidden nowadays by science itself, and this is what is done in England where there is political economy.

In the brilliant/appalling dream, a small boy brought up in the Church watches a horse beaten by a sadistic drunken peasant until the child attacks the peasant with his tiny fists. But the grown Raskolnikov plans to act like the awful peasant and kill — not out of drunken rage but according to his ‘rational’ theory, a theory that it is justified to take a life to save a hundred others.

As he walks the streets, we see again and again the contrast between utilitarian thoughts — why should I make a sacrifice to help someone, why should I care what happens to some wretch as it’s just ‘the laws of nature’ — and emotional revulsion at those ideas, then revulsion at the revulsion.

In his article ‘On Crime’, he articulates the central idea that the world divides into two sets: the ordinary, who obey the ordinary laws and morals, and the extraordinary, who do not and who ‘seek in various ways, the destruction of the present for the sake of the better’ (e.g Solon, Napoleon), who can ‘say a new word’. These people are justified by history in wading through blood and don’t even feel like they’re committing ‘crimes’ because they aren’t, they have a moral right to ignore the laws. Raskolnikov wants to prove to himself that he is one of these people.

When the fateful moment comes, though, he is, like a normal criminal, overwhelmed by the ‘eclipse of reason and failure of willpower’. The horror of the murder, and his incompetent execution of it, breaks his mind out of the utilitarian justifications he’d spun to himself. Later, he realises that he was a mockery of Napoleonic greatness, he’d failed to ‘surmount the barrier’ and in another dream he could not kill the old woman again — she sat in a chair and shook with laughter at his blows that could not land.

The awful Luzhin, a modern man of modern ideas, intends to marry Raskolnikov’s sister. Luzhin explains his modern ideas, science and economics. The old ideal of ‘love thy neighbour’ meant tearing your coat in half and ‘both left half-naked’. But science now shows that ‘everything in the world rests on self interest, therefore, in acquiring wealth solely and exclusively for myself, I am acquiring for all, and helping to bring to pass my neighbour’s getting a little more than a coat, and that not from private, isolated liberality, but as a consequence of the general advance.’ The awful Luzhin represents the modern radical — utilitarian egoism, aversion to private charity, and rejection of Christian self-sacrifice. When they discuss the growth of crime among the educated, Raskolnikov blurts out ‘But why do you worry about it… It’s in accordance with your theory — carry out logically the theory you were advocating just now and it follows that people may be slaughtered.’

One of the most extraordinary characters in all literature, Svidrigailov, has done what Raskolnikov could not do — push egotism to its logical conclusions in selfish depravity. He is pursuing Raskolnikov’s sister. His conversations with Raskolnikov are extraordinary, his final hours of thought and deranged dreams are horrific. It is talking to him that makes Raskolnikov realise that he had lost the right to distinguish himself morally from the appalling Svidrigailov. And he realises he will have to confess.

At one point in his discussions with Sonya, the ideal of Christian self-sacrifice, he blurts out, ‘Freedom and power but above all power! Power over all trembling creatures, over the ant-heap … that’s the goal’, thus revealing the truth about himself. When, after he confesses, she throws herself into his arms and says she’ll follow him to prison, it sparks his egoism and ‘satanic pride’.

Yet he finally admits to her that all his rationalising has been lies.

I wanted to murder without casuistry, to murder for my own sake, for myself alone! [to test] whether I was a louse like everyone else or a man… Whether I am a trembling creature, or whether I have the right… I didn’t murder either to gain wealth or to become a benefactor of mankind. Nonsense! I just murdered … and whether I became a benefactor to others, or spent my life like a spider catching everyone in my web and sucking the life out of others, must have been of no concern to me at that moment... I know it all now.

When she tells him to confess, he imagines the police mockery when he admits he didn’t even use the money —

Why they would laugh at me and would call me a fool for not getting it. A coward and a fool!

He tries to maintain that his ‘idea’ was valid, that the problem was that he had misjudged himself, that he had turned out to be ‘contemptible’ and not the sort of man to break the law to change the world.

But those men succeeded, and so they were right, and I didn’t, so I had no right to have taken that first step.

But finally he has to face the truth. In his final dream, Europe suffers a plague. Its victims believe they have reached new heights of understanding, of infallible scientific and moral conclusions. But of course with everyone making their own highly confident judgements they ‘could not agree what to consider good and evil’. All social cohesion is destroyed. This is the world of the West as Dostoyevsky saw it, a plague infecting Russia, a plague of amorality generating an intense egotism!

Porfiry, the detective, sums it up:

[The crime] is a fantastic, gloomy business, a modern case, an incident of today when the heart of man is troubled... Here we have bookish dreams, a heart unhinged by theories … a murderer who looks upon himself as an honest man, despises others, poses as a pale angel.

Its publication was a sensation. The final chapters were dictated to Anna, a stenographer. And as he was finishing it he proposed to Anna, his second wife. At 45 he was married again.

(I read Crime and Punishment aged about 14-15. It made a greater emotional impression on me than probably any novel has done with the partial exception of War and Peace. I had an old typewriter and typed out passages. I can’t remember why.)

Travel in Europe, writing The Idiot

After marrying he soon hurried abroad to escape creditors in April 1867. He gambled at roulette, lost everything, had to beg his new wife for money, lost that, and repeated such episodes in various stages across Europe. The episodes are all the more amazing given he’d written The Gambler. He wrote to Anna how he observed cold-blooded players winning consistently and tried to copy them but after a while his Russian character broke out and doomed him to disaster! He even pawned their wedding rings. And the whole nightmare was interspersed with his terrible epileptic fits. Their letters are terrible to read.

On these travels he also had his famous row with Turgenev, whom he owed money from a previous gambling spree. In 1867 Turgenev published Smoke, which caused an even bigger storm than Fathers and Sons. In it he attacked those on left and right who argued that Russia has a special destiny. A character, Potugin, declares that if Russia were to disappear from the earth nothing would be disarranged, for even the samovar, woven bast shoes, and the knout ‘were not invented by us’!

The two gave different accounts of the row but in Dostoyevsky’s, Turgenev was violently anti-Russian, pro-German, and atheist. Dostoyevsky denounced Germans as ‘rogues and swindlers’. In a letter to a friend, he wrote that his spitefulness might ‘make an unpleasant impression’ but he couldn’t help it — ‘it is impossible to listen to such abuse of Russia from a Russian traitor’. He was also enraged that Turgenev was proud of being an atheist:

But my God, Deism gave us Christ, that is, such a lofty notion of man that it cannot be comprehended without reverence and one cannot help believing this ideal of humanity is everlasting! And what have they, the Turgenevs, Hertzens, Utins, and Chernyshevskys presented us with? Instead of the loftiest, divine beauty, which they spit on, they are so disgustingly selfish, so shamelessly irritable, flippantly proud, that it’s simply incomprehensible what they’re hoping for and who will follow them.

The confrontation soon became widely known and Dostoyevsky would give a fictionalised version in The Devils with Karmazinov-as-Turgenev in a brutal satire (particularly see the scene in Part II, Chapter VI). Turgenev’s manners, his preference for living in Europe, his attacks on Russian culture, the egoism of the essay on watching an execution — so much of Turgenev is pasted on to Karmazinov. Turgenev was responsible for the prestige of Bazarov. Dostoyevsky makes Karmazinov responsible for the prestige of the monstrous Peter Verkhovensky.

In Geneva he watched revolutionaries discuss the future. Bakunin and others called for the destruction of all centralised states, the end of Christianity, the end of capital and a United States of Europe organised on a new basis. Dostoyevsky summarised it:

And most importantly, fire and sword — then after everything has been annihilated, then, in their opinion, there will, in fact be peace.

Such experiences contributed to The Devils.

Over 1867-9 he traveled Europe with Anna and gradually formed his ideas for The Idiot, throwing out an entire draft and many different plans. His epileptic seizures affected his memory and made him fear he was in decline artistically. Many letters from this time concern his view that, in a century’s time, Russia and its Church would bring a ‘grandiose renovation for the entire world’. In 1868 he had a baby daughter who died. He was crushed by poverty, by dreadful grief, by exile from Russia and by the pressure to finish The Idiot while his heart was broken. (Cf. chapter 40 in Frank.)

Writing The Devils

Kirilov: Then history will be divided into two parts: from the gorilla to the annihilation of God and from the annihilation of God to —

Narrator: To the gorilla?

Kirilov: To the physical transformation of the earth and man. Man will be god. Hell be physically transformed. And the world too will be transformed… Everyone who desires supreme freedom must dare to kill himself… He who dares to kill himself is a god…. I can’t think of something else. All my life I think of one thing. God has tormented me all my life,’ he concluded suddenly with amazing frankness.

The Devils, Dostoyevsky (p126)

The revolutionary despises all doctrines and refuses to accept the mundane sciences, leaving them for future generations. He knows only one science: the science of destruction… The object is perpetually the same: the surest and quickest way of destroying the whole filthy order… Night and day he must have but one thought, one aim – merciless destruction…

[T]he degree of friendship, of devotion, and of other obligations toward … a comrade is measured only by his degree of utility in the practical world of revolutionary pan-destruction.

The Catechism of a Revolutionary, Nechayev (1869)

The will to destroy is also a creative will.

Bakunin

After The Idiot he immediately started thinking about what became The Devils and he wrote of his determination to return to Russia and ‘my indispensable and habitual material — Russian reality … and the Russians’.

He started The Devils in 1869, its serialisation in Moscow began in 1870, he finally managed to return to Russia in July 1871, and its publication finished in 1872.

From Florence he started writing letters to friends describing the themes and characters that would become The Devils and Karamazov.

What I am writing now [Devils] is a tendentious thing. I feel like saying everything as passionately as possible. Let the nihilists and the Westerners scream that I am a reactionary! To hell with them. I shall say everything to the very last word.

He wrote to another friend that he was determined to express certain ideas ‘even if it ruins my novel as a work of art for I am entirely carried away by the things that have accumulated in my heart and mind’.

While writing Devils his notes and letters returned to themes and characters that ended up in Karamazov. He wanted to get Devils done so he could pay his debts and get going with Karamazov.

In Russian the title is Бесы which means ‘demons’. The demons are liberalism, rationalism, materialism, socialism, atheism.

In a letter to his friend Apollon Maykov, Dostoevsky alluded to the episode of the Gadarene swine as the inspiration for the title:

It is true that the facts have also proved to us that the disease that afflicted cultured Russians was much more violent than we ourselves had imagined, and that it did not end with the Belinskys and the Kraevskys and their ilk. But at that moment what happened is attested to by Saint Luke: the devils had entered into a man and their name was legion, and they asked Him: ‘suffer us to enter into the swine’ and He suffered them. The devils entered into the swine and the whole herd ran violently down a steep place to the sea and was drowned. When the people came out to see what was done they found the man who had been possessed now sitting at the feet of Jesus clothing in his right mind and those who saw it told them by what means he that was possessed of the devils was healed…

Exactly the same thing happened in our country: the devils went out of the Russian man and entered into a herd of swine, that is, into the Nechaevs et al. These are drowned or will be drowned, and the healed man, from whom the devils have departed, sits at the feet of Jesus ... and bear this in mind, my dear friend, that a man who loses his people and his national roots also loses the faith of his fathers and his God. Well, if you really want to know — this is in essence the theme of my novel. It is called Бесы and it describes how the devils entered into the herd of swine.

And he used Luke viii, 32-36, as an epigraph:

And there was there an herd of many swine feeding on the mountain: and they besought him that he would suffer them to enter into them. And he suffered them. Then went the devils out of the man, and entered into the swine: and the herd ran violently down a steep place into the lake, and were choked. When they that fed them saw what was done, they fled, and went and told it in the city and in the country. Then they went out to see what was done; and came to Jesus, and found the man, out of whom the devils were departed, sitting at the feet of Jesus, clothed, and in his right mind: and they were afraid. They also which saw it told them by what means he that was possessed of the devils was healed.

In Devils, he focused on the ‘Westernisers’ — the Russian liberals who wanted Russia to become a constitutional monarchy and the revolutionaries who opposed the aristocracy and capitalism. He thought that Pushkin’s famous Evgeny Onegin (published in the 1830s) represented the beginning of artistic representation of the crisis of the Russian spirit assailed by the West —

the very first beginnings of our agonising consciousness … and our agonising uncertainty as we look around us… This was the first beginning of that epoch when our leading men sharply separated into two camps [Slavophiles and Westernisers] and then violently engaged in a civil war… The scepticism of Onegin contained something tragic in its very principle, and sometimes expressed itself with malicious irony… [Onegin] does not even know what to respect though he is firmly convinced that there is something that must be respected and loved. But … he does not respect even his own thirst for life and truth… He becomes an egoist and at the same time ridicules himself because he does not even know how to be that.

We see the same type, but more malicious, in Lermontov’s classic A Hero Of Our Time. Stavrogin in The Devils would push the type to the logical conclusion. It’s very important to know — and is not well explained in some translations — that the novel that was published left out a crucial chapter. Dostoyevsky wrote a ‘confession’ of Stavrogin. Like some of the scenes with Svidrigailov in Crime and Punishment, it is dreadful to read, you can feel the horror coming with the little girl. His publisher was so appalled he absolutely refused to publish it. After arguments Dostoyevsky rewrote the novel to deal with the absence of the chapter. After the serialisation, Dostoyevsky did not want to battle the censors. The chapter was ignored until it was found in his papers fifty years later in the 1920s. Often now it is tacked on the end as an Appendix. But it is central to understanding Stavrogin.

A letter from someone who spoke to Dostoyevsky in the 1870s recalls how he once told a story of being in a children’s hospital as a child, where his father worked. He made friends with a nine year old girl. She was raped by a drunk ‘and she died pouring out blood’.

All my life this memory has haunted me as the most frightful crime, the most terrible sin, for which there is not, and cannot be, any forgiveness, and I punished Stavrogin in Demons with this very same terrible crime. (Frank, p450)

As he was writing The Devils, a revolutionary conspiracy in Russia was exposed, organised by Sergey Nechayev, a disciple of Bakunin (the founder of Russian anarchism). Nechayev was a seminariste, a divinity student, and attended lectures at St Petersburg University where he organised protests in 1868-9. In 1869 he’d gone to Switzerland where he joined Bakunin. He returned as a representative of the World Revolutionary Movement at Geneva and started organising Russian activists. ‘The end justifies the means’, he proclaimed to his allies. His Catechism of a Revolutionary became influential, was reprinted by the Black Panthers in the 1960s, and is still read by revolutionaries.

Nechayev and friends murdered one of their group, Ivanov, for disobeying orders. Dostoyevsky’s description of Shatov’s murder follows that of Ivanov. Nechayev, like Verkhovensky in Devils, fled to Geneva. Ironically Bakunin broke with him for being a duplicitous fanatic. In 1872 he was arrested in Switzerland and sent to Russia where he was imprisoned. In many ways Nechayev seemed like the outcome of exactly the ideas Dostoyevsky had described in Crime and Punishment.

While Dostoyevsky was writing Devils, Nechayev remained at large. The trials and published documents furnished him with material. He found the prototype of Kirilov in Smirnov, one of Nechayev’s followers. He twisted the plot of Devils to fit some of the breaking news, leading to inconsistencies. Like with The Idiot, he abandoned and recreated one plan after another. And as usual he wrote it all short of funds and while having to deal with the stresses this caused.

In a recent preface to a new edition of Fathers and Sons, Turgenev had sided with the radicals. A lady had said to him ‘You are a Nihilist yourself’ and he wrote, ‘I will not undertake to contradict: perhaps the lady spoke the truth.’ Elsewhere he wrote that other than Bazarov’s views on art he ‘almost shares all his convictions’. Dostoyevsky’s anger at his own generation, including Turgenev, had been building for years. Now his rage poured out. In a characteristic tirade, he described in a letter ‘the mangy Russian liberalism preached by shitheads like the dung beetle Belinsky’.

As he wrote The Devils in 1870, Bismarck was smashing the French then the Commune took over Paris, the red flag flew, chaos spread. He wrote to a friend:

In essence, it is all the same old Rousseau and the dream of recreating the world anew through reason and knowledge … (positivism)… The burning of Paris is a monstrosity: ‘It did not succeed, so let the world perish because the Commune is higher than the happiness of the world and of France’… To them (and many others) this monstrosity doesn’t seem madness but, on the contrary, beauty. The aesthetic idea of modern humanity has become obscured…

If Belinsky, Granovsky, and that whole bunch of scum were to take a look now, they would say: ‘No, that is not what we were dreaming of, that is a deviation; let us wait a bit, and light will appear, progress will ascend to the throne, and humanity will be remade on sound principles and will be happy!’ There is no way they could agree that once you have set off down that road, there is no place you can arrive at other than the Commune.

Dostoyevsky found the way that radicals like Belinsky denounced Christ and thought of themselves as higher types of man for having denounced him to be utterly repulsive. When Turgenev wrote an essay about an execution, Dostoyevsky was enraged that Turgenev focused on his own feelings rather than the sufferings of the executed, for his own ‘peace of mind, and that in sight of a chopped-off head!’ Thinking through further on Turgenev, he wrote of what he called ‘the gentry-landowner literature’:

It has said everything that it had to say (superbly by Lev Tolstoy). But this in the highest degree gentry-landowner word [i.e Tolstoy] was its last. There has not yet been a new word…

He intended The Devils to be a new word.

After the first few chapters were published, a friend wrote that the characters were ‘Turgenev’s heroes in their old age’ and Dostoyevsky replied, ‘That is brilliant! While writing, I myself was dreaming of something like that’.

One of the themes in The Devils is the confrontation between generations which is also a confrontation between Dostoyevsky and Turgenev. Stepan Trofimovich Verkhovensky is a Romantic Idealist of the 1840s. Dostoyevsky drew partly on Granovsky, a historian of the 1840s who died in 1855 and was already half-forgotten by 1870. Herzen had described how he and Belinsky had, in summer 1846, become militant atheists but Granovsky had not followed them: ‘For me personal immortality is a necessity’, Herzen claimed Granovsky said. In the 1850s, younger intellectuals such as Chernyshevsky viciously attacked people like Granovsky and his generation as weak, indecisive, incapable of leading Russia or anybody to a new world. Dostoyevsky makes such a figure the father of the appalling cold-blooded revolutionary Peter Verkhovensky.

But there is also in Stepan Trofimovich something of Herzen himself. Herzen rejected the Chernyshevsky path and said of it, in words that echo in Stepan Verkhovensky —

farewell not only to Thermopylae and Golgotha but also to Sophocles and Shakespeare, and incidentally to the whole long and endless poem which is continually ending in frenzied tragedies and continually going on again under the title of history.

Herzen’s plea for the two generations to advance together was rejected contemptuously and violently. He was attacked and he struck back denouncing Bakunin and his followers — their force of destruction would wipe out not just property but ‘the peaks of human endeavour’.

And Stepan Verkhovensky says of What Is To Be Done?, like Herzen:

I agree that the author’s fundamental idea is a true one but that only makes it more awful. It’s just our idea, exactly ours, we first sowed the seed, nurtured it, prepared the way, and indeed what could they say new, after us? But heavens! How it’s all expressed, distorted, mutilated… Were these the conclusions we were striving for? Who can understand the original idea in this?

And after he is mocked by the young generation, Stepan Verkhovensky says, deliriously:

But I maintain, I maintain that Shakespeare and Rafael are higher than the emancipation of the serfs, higher than Nationalism, higher than Socialism, higher than the young generation, higher than chemistry, higher than almost all humanity because they are the fruit, the real fruit of all humanity, and perhaps the highest possible fruit! A form of beauty already attained without whose attainment I, perhaps, would not consent to live.

The Devils is extraordinary for the astounding realism of the characters, the insight into the revolutionary psyche, and the exploration of themes that are as fundamental today as in 1870. Many said at the time that the characters in The Devils were too pathological. From our perspective, we can see that they were prophetic.

Bakunin himself worked with Nechayev and initially praised him highly. Then Nechayev fled Russia for Switzerland where he started applying his methods to Bakunin and his friends. Suddenly terrorist tactics and the abandonment of bourgeois morality were not so popular! Bakunin found it necessary to write urgently warning his revolutionary allies against their own protégé:

It is equally true that [Nechayev] is one of the most active and energetic men I have ever met. When it is a question of serving what he calls the cause, he does not hesitate; nothing stops him, and he is as merciless with himself as with all the others. This is the principal quality which attracted me and which impelled me to seek an alliance with him for a good while. Some people assert that he is simply a crook but this is a lie! He is a devoted fanatic, but at the same time a very dangerous fanatic whose alliance cannot but be harmful for everybody…

[H]is methods are detestable… He has gradually succeeded in convincing himself that, to found a serious and indestructible organisation, one must take as a foundation the tactics of Machiavelli and totally adopt the system of the Jesuits — violence as the body, falsehood as the soul.

Truth, mutual confidence, serious and strict solidarity only exist among a dozen individuals who form the sanctum sanctorum of the Society. All the rest must serve as blind instrument and as exploitable material… It is allowed — even ordered — to deceive all the others, to compromise them, to rob them, and even, if need be, to get rid of them — they are conspiratorial fodder.

Bakunin goes on to describe in detail the sorts of tricks and lies Nechayev will deploy: he will spy on you and steal your documents to learn secrets for blackmail. When we caught him doing this, ‘he had the nerve to say — ‘Well, yes, that’s our system. We consider as enemies all those who are not with us completely, and we have the duty to deceive and compromise them’. He will sow discord among friends. He will seduce your wife and daughter ‘to make them pregnant, in order to tear them away from official morality and to throw them into a forced revolution against society.’

He is terribly ambitious without knowing it, because he has ended by identifying the cause of the revolution with that of himself — but he is not an egotist in the banal sense of the world because he risks his life terribly and leads the existence of a martyr full of privations and incredible anxiety.

He is a fanatic and fanaticism carries him away to the point of becoming an accomplished Jesuit... With all this [Nechayev] is a force because of his immense energy…

Their system, their joy, is to seduce young girls: in this way they control the whole family.